From Tramps to Kings: 100 Years of Zulu

Zulu: A Short History

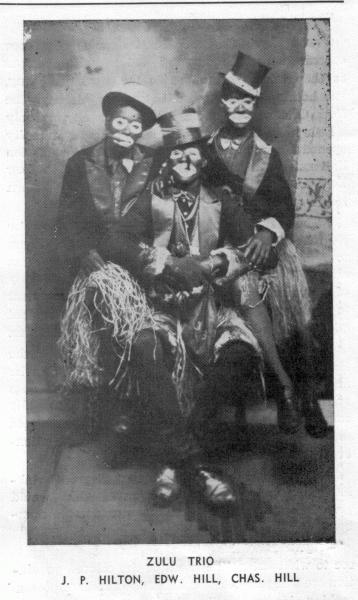

Zulu traces its origins to 1909 when the founders paraded as a marching club. Between 1912 and 1914, the group had adopted the name “Zulu” and an African theme for their costumes. Their inspiration was a vaudeville skit titled “There Never Was and Never Will Be a King Like Me,” in which the characters wore grass skirts and dressed in blackface – a common practice in vaudeville theater, for both black and white performers. The costume also included black-dyed turtlenecks (known as “goosenecks”) and tights purchased from theatrical supply stores. Some members used Spanish moss from nearby swamps for wigs and rabbit fur as trim. Boots were painted gold.

The origins of the famous Zulu coconut – hand-painted and decorated coconuts used as parade “throws” and souvenir – are not well documented, but Zulu historians believe that these prized items date back to the early 1910s.

In 1916, the group formally incorporated as the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club in the mold of countless African-American benevolent associations that have provided essential social services, such as funeral costs, for their members since the 19th century. In fact, the earliest Zulu parades were sponsored by African-American businesses, such as the Gertrude Geddes Willis Funeral Homes and Good Citizens Insurance Company.

From 1923 to 1933, male members had masked as the Zulu queen, following a common Mardi Gras tradition of men appearing as women, often to comic effect. When the Ladies Auxiliary formed in 1933, the Zulu club began selecting queens from this group, a practice that continued into the 1970s. In 1933, the first female queen debuted at the official toasting site of Geddes and Moss on Jackson Avenue, a tradition that continues to the present day. In 1948 Zulu became the first Mardi Gras organization to feature a queen in its parade, when Edwina Robertson and her maids rode on the first Zulu queen’s float.

Zulu made civil rights history in 1969 when the city granted the club permission to parade on Canal Street, the route historically reserved for white carnival parades. This route change, not typically viewed as a civil rights victory, was significant and symbolic in that an African-American carnival organization became part of the city’s official Mardi Gras festivities.

The 1970s and 1980s brought even greater popularity. Under President Roy Glapion Jr., who later became a city councilman, Zulu made greater efforts to support the community as part of its mission. Finding inspiration in its benevolent society origins, Zulu members volunteered to feed the needy at holiday time and organized fundraisers for sickle-cell anemia research as the Zulu Grinders Can Shakers. The club also organized the Zulu Ensemble gospel choir, reflecting the spiritual enthusiasm of many members.

This centennial year provides an excellent opportunity for the Louisiana State Museum and Zulu to celebrate the club’s rich history, its accomplishments, and its dedication to community service.

Zulu Characters

The Zulu characters have been a part of the parade since the very beginning, starting with the king. Through the years, Zulu developed additional characters including the Witch Doctor, the Big Shot of Africa, the Ambassador, the Mayor, the Province Prince, the Governor, and Mr. Big Stuff.

The Witch Doctor was created in the 1920s. He is known as the sorcerer asking for safety, good health, and pleasant weather on Mardi Gras.

The Big Shot dates to 1930. His role is to “outshine” the king for attention. He dresses very flamboyantly and stands out from other members with his large cigar, glass doorknob for a diamond ring, and derby hat.

Mr. Big Stuff was created in 1972 and named after a hit record by New Orleans soul singer Jean Knight. He’s known as a ladies’ man who dresses with class and style.

But some characters were short-lived. In the 1930s and 1940s, Zulu parades featured characters like Chief Ubangi, Zambango the Snake Man, the Head Hunter, and Jungle Jim.

Louis Armstrong, Zulu King

Growing up in the New Orleans neighborhood where Zulu began, jazz legend Louis Armstrong had a dream of becoming a member and possibly king. He was named an honorary member in 1931 and saw his boyhood dream of becoming a Zulu king fulfilled in 1949.

Armstrong’s reign was an international media story, and his image as king graced the cover of Time magazine. “Oh we had a ball at City Hall,” Armstrong later wrote “[Mayor Chep Morrison’s] office was packed and jammed with the press – his friends and my friends, and I’m telling you . . . we really did pitch a boogie woogie.”

The day also had a lasting impact. The club has honored Satchmo’s place in Zulu history many times through a doubloon, a souvenir booklet, and a poster. One of Zulu’s most popular floats today features a giant figure of Louis Armstrong.

In 1952 Louis Armstrong wrote a four-page letter to a reporter for the New Orleans Item describing his historic reign as Zulu. Now in the collection of the Louisiana State Museum, the letter is both a priceless piece of history and a wonderful example of Armstrong’s exuberant writing style.

Download Louis' Full Letter (PDF)

Additional Resources

Press Release from 2009 exhibition, From Tramps to Kings: 100 Years of Zulu (PDF)

Fact Sheet from 2009 exhibition, From Tramps to Kings: 100 Years of Zulu (PDF)

History of Zulu (PDF)