Louisiana and the Mighty Mississippi River

As a symbol and in reality, the Mississippi is deeply rooted in America’s vision of itself. For centuries, the river has been the lifeblood of the country, serving and inspiring its people. This online exhibition—Louisiana and the Mighty Mississippi River—explores the unique legacy of this famous waterway.

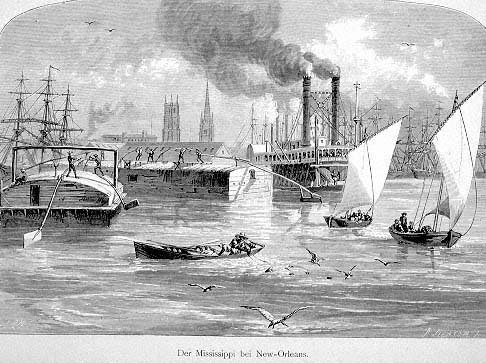

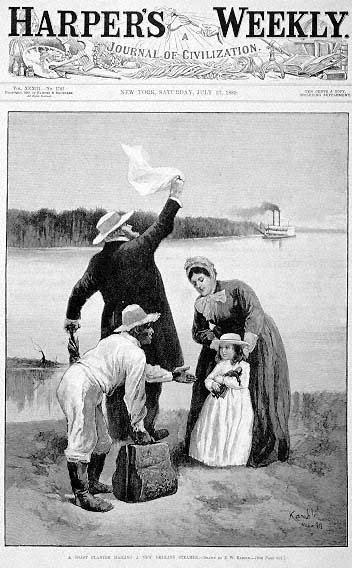

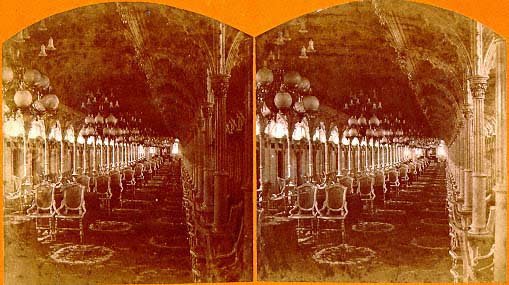

The roles played by the Mississippi in the evolution of the U. S. are many: the river is integrally linked to progress in commerce, technology, and culture. At the heart of this history is the story of transportation—a tale of wealth, romance, and adventure associated particularly with this state. Early Louisiana was a strange mix of raucous frontier life and European sophistication. These contrasting elements, reflected in a rough-hewn 1840 pirogue and views of New Orleans as a cosmopolitan capital, set the stage for the exhibition.

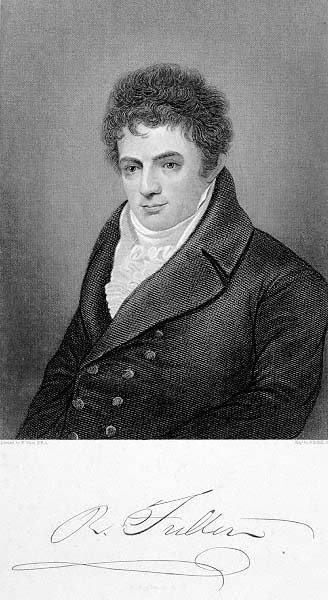

Robert Fulton is known as the inventor of the steamboat. In reality, Fulton's invention was modeled after several other prototypes that paved the way for his success. He began his career as an artist, but eventually turned to mechanical engineering where his interests included canal dredging, bridge construction, rail transport, and submarines.

In 1803 while in Paris, he built a prototype of a steamboat with the help of then American minister to France, Robert R. Livingston. In 1807, he brought this technology to the United States by launching the Clermont on the Hudson River in New York. In 1811, his design for the steamboat New Orleans was built by Nicholas I. Roosevelt who helped pilot the vessel from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. This event opened the River up to early steamboat traffic.

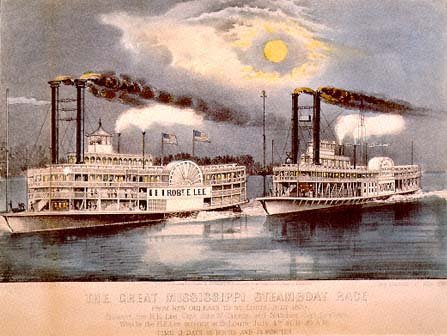

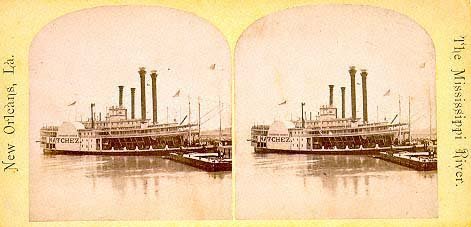

Ever since two steamboats passed each other on the Mississippi River, pilots and owners have wanted to compete to see whose boat was faster and could carry more cargo. Perhaps the most famous steamboat race occurred in June 1870 from New Orleans to St. Louis between the Natchez VI and the Robert E. Lee. That month, the Natchez had made a record-breaking trip from New Orleans to St. Louis in 3 days, 21 hours, and 58 minutes. Captain John W. Cannon of the Lee decided that the Natchez success could not go unanswered. While waiting for the Natchez to return to New Orleans, he readied the Robert E. Lee for a race by stripping her of excess weight and declining any passengers or cargo.

Captain T. P. Leathers of the Natchez welcomed the challenge but refused to lighten his burden. The two boats left New Orleans with the Robert E. Lee slightly ahead. During the race, Captain Cannon had arranged for barges to be floated alongside of the Lee to expedite the refueling process. The Natchez was forced to do the same, but only after some time had passed. The Robert E. Lee won the race by several hours, but the Natchez had been stuck on a mudflat for six hours. The Natchez might have won the race if Captain Leathers had unloaded his cargo and passengers.