Colonial Louisiana

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History, 1699–1877

The promise of prosperity brought people to Louisiana, voluntarily or by force. Among the many ethnic groups in colonial Louisiana were people of French, Canadian, Spanish, Latin American, Anglo, German, and African descent. No one of these cultures dominated in the eighteenth century, and along with Native Americans, they provided the initial ingredients for Louisiana's famous "gumbo" of cultures.

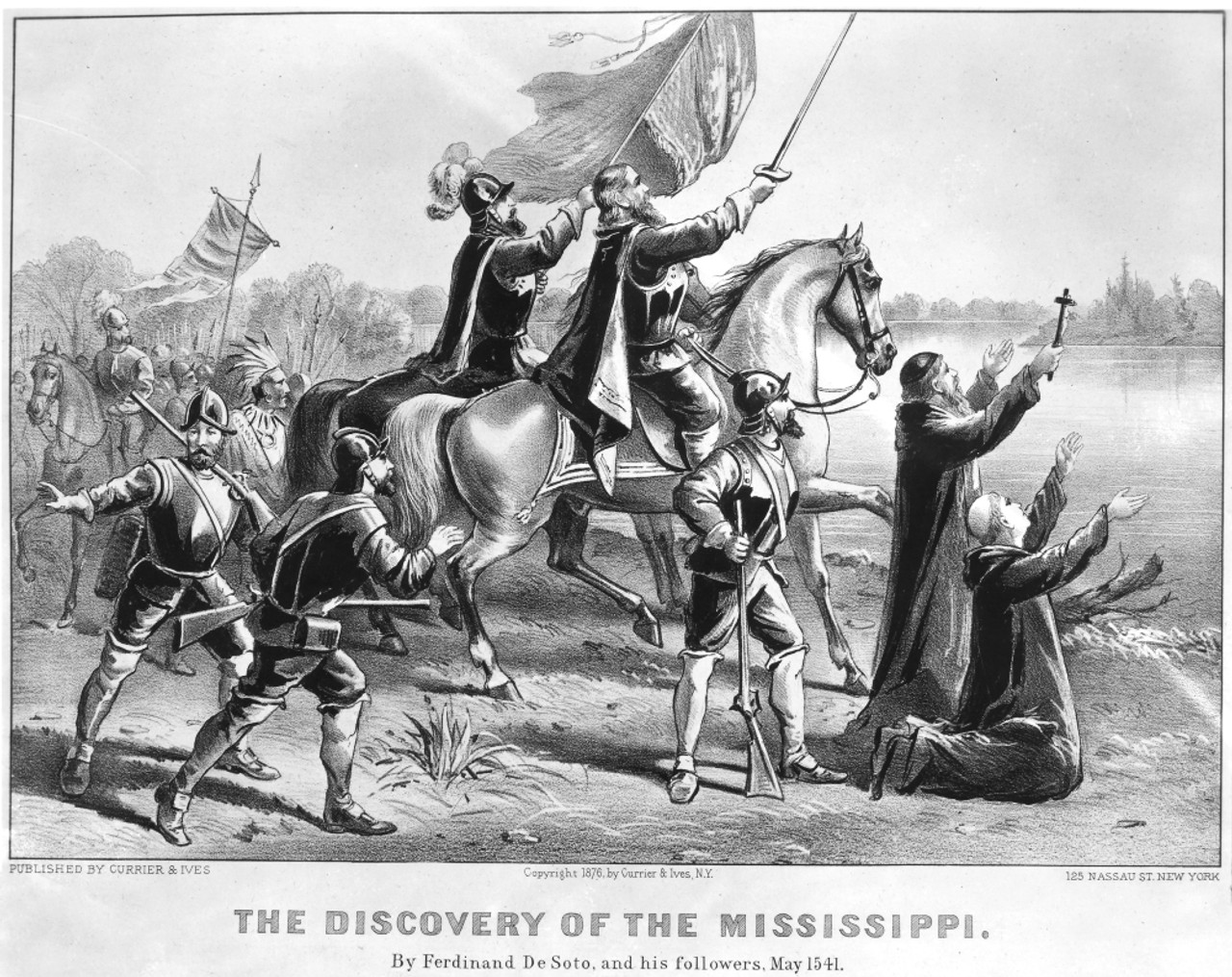

Spaniards were the first to venture into the Mississippi River region. Hernando de Soto's overland expedition in 1542 was the first to confirm European discovery of the mighty river, but the hostile climate, wildlife, and geography convinced Spain to look elsewhere for precious metals and fertile soils. Louisiana was ignored for nearly a century and a half, until France's King Louis XIV, the "Sun King," began encouraging exploration of the Mississippi River in order to enlarge his own empire and halt Britain's and Spain's expansion. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, reached the river's mouth and proclaimed possession of the river and all the lands drained by it for France, naming this vast expanse "Louisiane," or "Louis' land."

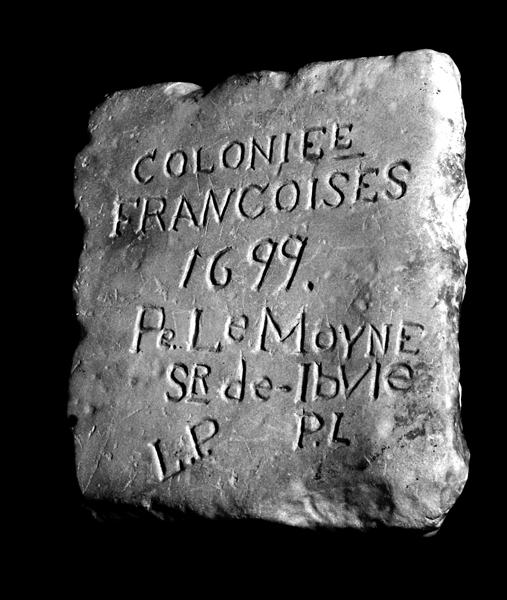

In 1699, Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville, sailed into the Gulf of Mexico. His party reached the mouth of the river on Shrove Tuesday and celebrated Mardi Gras with a mass and Te Deum. However, Iberville chose to establish a permanent settlement on the Gulf Coast rather than on the river because of the fear of large ships getting stuck coming into the mouth of the river.

| Timeline of European Rulers | |

|---|---|

| 1699–1712 | Crown |

| 1699–1769 | France |

| 1712–1731 | Proprietary |

| 1731–1769 | Crown |

| 1769–1803 | Spain |

| 1769–1803 | Crown |

| 1803 | France |

| 1803 | Republic |

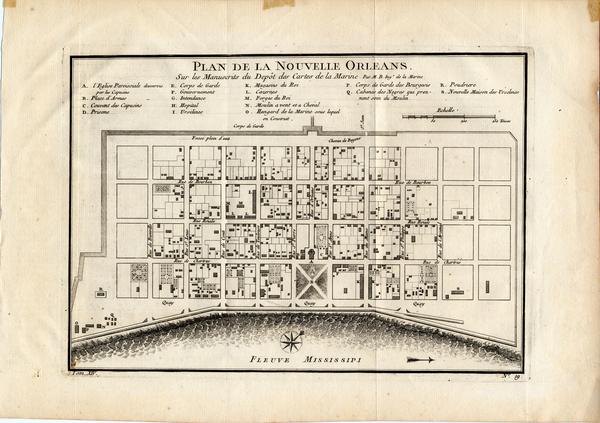

While Iberville returned to France for additional provisions and settlers, his brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, continued to explore the Mississippi River, but Iberville still insisted that the river was not navigable. Bienville had to delay creating a permanent settlement on the lower Mississippi River until 1718 when he founded the city of New Orleans on a crescent-shaped section of the river 100 miles from the mouth. He named France's newest settlement in honor of the ruling regent, the Duc d'Orleans.

The site chosen for New Orleans had many advantages. Because it sits where the distance between the river and Lake Pontchartrain is shortest, Louisiana Indians had long used the area as a depot and market for goods carried between the two waterways. The narrow strip of land also aided rapid troop movements, and the river's curve slowed ships approaching from downriver and exposed them to gunfire.

Contact among Louisiana's most numerous inhabitants—whites, Indians, and Africans—was a three-way exchange. No one racial or ethnic group dominated during much of the colonial period. Native Americans made up the largest segment of Louisiana's population in the 1700s and shared food, medicines, material goods, and building and recreational practices with colonists.

Africans were also a powerful cultural force in Louisiana, mainly because they were introduced in large numbers during short time periods and came mostly from one region in West Africa and thus related more easily to one another.

Through trade and gift-giving, Native Americans acquired a taste for such European items as sophisticated weapons, liquor, cloth, glass beads, and other trinkets. Europeans used their access to the supply of these goods to increase Native American dependency on them.

While a French colony, Louisiana was governed alternately by the crown and by several chartered proprietors, who contracted with the crown for administration of the colony and a trade monopoly in exchange for settlers and slaves to supply the colony with goods. Antoine Crozat was Louisiana's first proprietor of Louisiana from 1712 until 1717, when he resigned and the crown turned the colony over to John Law, who created the corporation called the Company of the Indies in 1719 to govern Louisiana. Beset by failed crops, Indian wars, slave insurrections, and financial disaster, the Company of the Indies returned the colony back to the crown of France, who administered it until 1763, when it turned Louisiana over to Spain.

Louisiana was a Roman Catholic colony with a close relationship between church and state, priests, and politicians. In general, the church and state worked together to preserve the prevailing order. The French and Spanish kings paid the salaries of the clergy and selected bishops. The Jesuits in particular served as frontier diplomats and expanded France's empire in North America by bringing Christianity to the Indians. The Capuchin and Ursuline orders were also active in administering to the needs of Louisiana colonists.

Although most settlers in Louisiana were of the Catholic faith, a few were Protestants or Sephardic Jews. Royal policy in France and Spain prohibited non-Catholics from living in the colonies, but especially in frontier regions like Louisiana, enforcement was scarce. At times Protestants were even encouraged to settle in Louisiana.

Early Louisiana's most active churchgoers were African Americans. Although in 1800 about an equal number of blacks and whites lived in New Orleans, twice as many blacks were baptized in St. Louis Cathedral, the main church in colonial Louisiana, which still stands on Jackson Square in New Orleans, next to the Cabildo. Many Africans and creoles (American-born) continued to practice their African religious rituals covertly or merged them with Catholic beliefs.

All trade conducted with the colony was supposed to take place with the mother country, thereby keeping profits within the imperial system. This practice did not work well in Louisiana at first, however, because Louisiana had too few desirable products to export and too few people to exploit what natural resources existed. Toward the end of the colonial period, an export-directed economy finally succeeded for Louisiana, and the colony benefited from the exportation of such crops as cotton, sugar, tobacco, indigo, and rice and from natural resources, like timber, furs, hides, and fish.

Louisianians used earnings from the export of cash crops and natural resources to purchase imported slaves and merchandise, primarily manufactured goods and foods they did not produce themselves, such as textiles, furniture, and household furnishings. For most of the colonial period wholesale merchants imported goods and slaves first from France and later from Spain. Smuggling goods from European and American ships became prevalent and remained so, even when trade restrictions in the colony were lifted.

New Orleans quickly became the hub of a new regional trade network, with goods flowing into the city along the surrounding waterways to be sold in the many shops and market stalls throughout the city. Louisianians also began to manufacture goods and provide services that could not legally or even illegally be obtained from other countries and colonies. During this period, most manufacturing involved the processing of crops and natural resources and the production of articles needed in the home: furniture, leather goods, clothing, utensils, and iron implements. In 1795 about half of New Orleans carpenters, joiners, shoemakers, silversmiths, gunsmiths, and seamstresses were free blacks.

Even though the people who inhabited colonial Louisiana--whites, blacks, and Indians--commonly mingled and shared social values and recreational practices, many also planned or participated in several military actions, either as instigators or defenders. In response to the invasion of settlers and slaves who disrupted traditional native lifestyles, some Louisiana Indians waged war. One of the most deadly was the Natchez Massacre and War (1729-1731), during which Natchez warriors attacked a French settlement, killing hundreds of white colonists and capturing nearly 300 black slaves. In retaliation, the French governor sent white and black troops and Choctaw warriors allied with the French to attack Natchez settlements, virtually exterminating the entire Natchez society.

A Medley of Cultures: Louisiana History, 1699–1877

Online Exhibition

The Louisiana Purchase

Territory to Statehood

The Battle of New Orleans

Disease, Death, & Mourning in Antebellum Louisiana

Agrarian Life in Antebellum Louisiana

Urban Life in Antebellum Louisiana

The Civil War

Reconstruction: A State Divided

Reconstruction: Change and Continuity in Daily Life