The Lore of Flying Africans

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

From the era of slavery through the present, flying figures have remained essential themes in African American folklore. Enslaved Africans, who were kidnapped and brought to the New World, passed down tales of tribal members or ancestors who had the power to soar through the skies or walk on water and return to freedom in Africa. This vital mythology also contributes to ideas about the afterlife, with flying spirits returning to the homeland.

As Africans became Christianized, beliefs in flying figures persisted and evolved. In Christianity, the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit, and in funerary art conveys that the deceased is being carried to heaven. Such iconography would have connected with enslaved West Africans, for whom birds represent ashé, the power to make things happen This alignment of symbol and belief continues to this day, as in the tradition of waving a white handkerchief in second-line dances at New Orleans jazz funerals, a practice that can be interpreted to represent a convergence of Christian and traditional Yoruba iconography. The imagery remained in songs and hymns, retaining a mystic connection to flight. For example, the hymn “I’ll Fly Away,” which originated elsewhere, resonated deeply with African Americans in New Orleans and became a standard in the New Orleans brass band funeral repertoire.

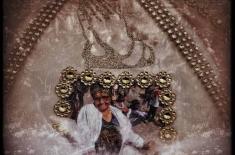

In Mardi Gras Indian suits, the imagery of flight has also been applied to scenes of political allegory. Tyrone Casby, Big Chief of the Mohawk Hunters, incorporated a winged President Barack Obama in symbolic battles with flying dragons into two of his suits, one at the beginning of Obama’s first term and a second one as he left office. In these examples, as in other representations, heroic flying figures represent an invocation or recognition of spiritual agency in service of social justice.

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

Online Exhibition