Native American Inspiration

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

How did African Americans in New Orleans come to incorporate Native American personae into their Mardi Gras masking rituals? It is impossible to know exactly when that happened, but the multicultural gatherings at Congo Square, which included Indigenous people, contributed to this cultural blending. At this weekly convergence to sell goods, sing, and dance, enslaved and free people of African descent kept alive West and Central African masquerade traditions and Afro-Caribbean spiritual and performance practices, all while absorbing the influences around them. Both the enslaved and free people of color encountered Native Americans not only at Congo Square but multiple places in the region—in hidden settlements in the swamp where Natives and escaped enslaved people banded together, at Choctaw stickball games in the city, and at other city marketplaces.

As Mardi Gras took its modern form after the Civil War, Black New Orleanians continued to claim the ritual of carnival as their own even as the white power structure relegated them to second-class citizenship. Excluded from elaborate parades and fancy balls, they created their own celebratory practices and also protested their marginal status through costuming, dancing, chanting, and secret rituals. Some adopted the dress of Native Americans, who represented resistance to white control. Some trace this tradition to the colonial period, when enslaved people ran away and joined Native tribes in the swamps. Later, people of African descent honored this help by incorporating Native representations into their carnival masquerade. They also took their cues from images of Native Americans in American popular culture, such as magazines, vaudeville, and, later, movies.

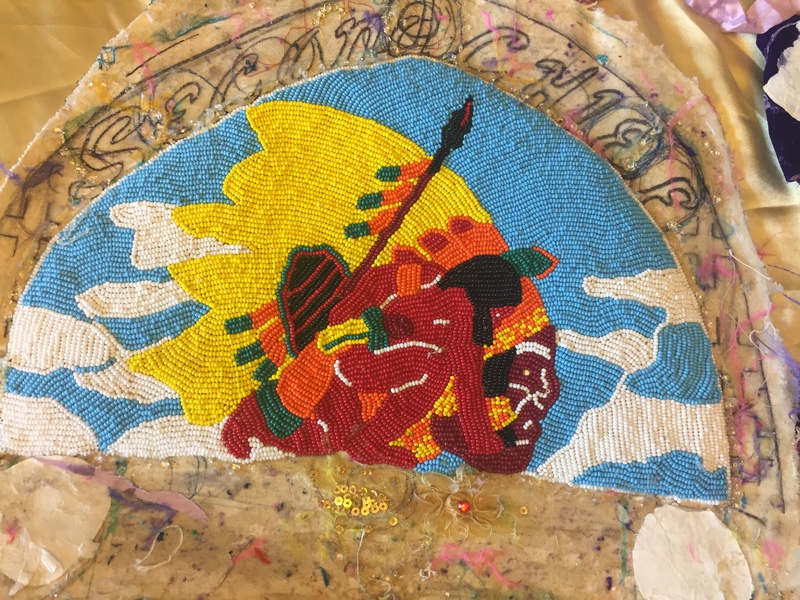

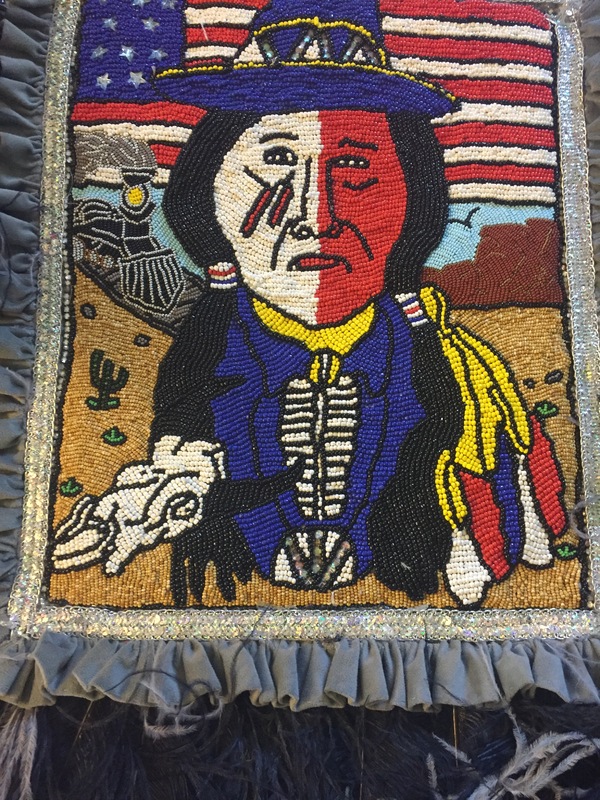

The foundation of Black masking Indian visual storytelling is rooted in Native American resistance. Many of their suits showcase battle scenes depicting victorious Native Americans at war with U.S. soldiers. Other imagery features animals that Native Americans imbue with great power as well as romanticized tribal life. And some, like those created by Wild Tchoupitoulas Second Chief Floyd Track, are reflective of Native American spiritual beliefs.

Track’s grandmother Lily Murphy was part Native American and taught him to hunt, fish, and plant food at her Napoleonville, Louisiana, home. He learned about masking Indian from his father, who was a member of the Wild Squatulas gang and read stories about Native Americans to him. As a spiritual person, Track was intrigued by the dynamics of Native religion. A veteran of the civil rights movement in New Orleans, Birmingham, and Mississippi, he continues to be inspired by the history of Native American resistance, their support of African Americans, and some of their spiritual beliefs. The vignettes he has depicted in his suits’ patches include the transformation of the human body into animal form, the ability of Indians to communicate with legendary chiefs of the past who defeated white American soldiers, a Native American confronting the Grim Reaper in a battle, Native burial practices, and the release of the spirit from the body. In these suits, which celebrate the ability of Native Americans to survive life’s perils, Track offers visual allegories in support of the continued struggle of African Americans to achieve equal opportunity and justice.

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

Online Exhibition