The Sewing Uprising

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

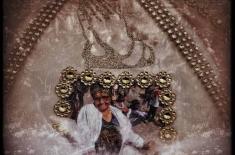

Black masking Indians are now among the most iconic figures of New Orleans. Originally embellished simply, their suits have evolved into stunning outfits. Although the tradition appears to be Native American, it is also firmly grounded in West African aesthetic and spiritual influences. While some who suit up in elaborate beaded, sequined, and bejeweled attire have Native ancestry, others honor the spirit of cooperation and refuge that Native Americans provided to enslaved people. Many also see common civil rights struggles with Native Americans, and this narrative of resistance informs their designs. In addition, masking as Indians became a communal and spiritual experience. The work of creating suits is a contemplative process of worship in anticipation of the spiritual transformation that happens when they put on the suit and step out onto the street.

What is traditional Black masking Indian attire? The answer has changed over time. In the early twentieth century, Black masking Indians used turkey feathers, gemstones scavenged from women’s evening dresses, ribbons bought from Sicilian American dry-goods stores, bottle tops, and other found items. These suits were light enough to enable maskers to “play” Indian as they chased other Black masking Indian groups through their neighborhoods.

By 1976, when Maurice Martinez debuted his groundbreaking film Black Indians of New Orleans, the suits had become much more elaborate, structurally complex, and more ornate with intensely colored feathers. Also apparent were a “downtown” style of three-dimensional symbolic designs, as exemplified by Allison “Tootie” Montana (1922–2005), Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas, and a contrasting “uptown” style featuring beaded flat visual elements that often depict Native American heroic vignettes, as seen in the patches of Floyd Track, Second Chief of the Wild Tchoupitoulas, in this exhibition.

And it wasn’t just the appearance of the suits that was evolving. In the 1960s, some Black masking Indians turned their gaze to Africa for cultural inspiration to express their political views. Some innovators, including Donald Harrison Sr., Victor Harris, Derrick Magee, and Ferdinand Bigard, began to challenge the standards in place, sewing new imagery that drew upon Christian and African spirituality. Influenced by the Black Power movement and a growing interest in traditional African religions, this new visual language drew strong criticism from some community leaders, who disapproved of these disruptions of traditional forms. Nonetheless, these spiritual expressions multiplied in the decades since then, becoming a significant strand of Black masking in New Orleans.

Mystery in Motion: African American Spirituality in Mardi Gras

Online Exhibition